A few months ago, I wanted to host files stored on a portable hard disk on the

public internet. These files were just some photos and videos that I wanted to

share with some of my cousins. Nothing fancy, just a webdav server using

rclone would

suffice—a very ad-hoc setup as you can see. I wanted it to be reachable

at share.prithu.dev to give it a short and friendly rememberable name. I used

the RPi 4 to be the host machine, attached the hard drive to one of it’s usb

ports, mount’d the drive at /mount/hdd and ran:

rclone serve webdav --user foo --pass secret --addr 0.0.0.0:8080 /mount/hdd/shared-dir

This is simple enough. Now, all I need to do is, using port-forwarding rules on

my router, expose this port to the world and point share.prithu.dev to my

home IP address, and bob’s your uncle … or is he? Well, the glaring problem

here is me exposing my home IP address—which is, to say the least, a bad

practice and something that I want to avoid. Also, there’s the problem of

dynamic IP of home broadband, but that’s a fairly easy problem to solve by

writing a script to update the DNS records every X minutes.1

Another solution is I can use one of my VPSs with a static public IP as a proxy

between the RPi and the internet—effectively hiding my home IP from the

internet. I will also not have to worry about the changing home IP. One way to

do this is using good ol’ ssh tunnels (port forwarding) and forward the remote

port to my RPi. In my experience however, I have found ssh tunnels to be a

little unreliable, especially when it comes to spotty home broadband

connection, due to which the connection breaks and you will have to either

restart the client or write a script or a service to restart the client

automatically. SSH tunnels are good for quick one-off tasks though. They can be

a life saver—that is, If you can remember the right syntax of -R and -L

options without referring to the man page (now that’s a challenge!). I wanted

the server to be reliably hosted for as long as it was required with minimum to

no maintenance from my side. So, I thought to try my hands on wireguard with

NAT on the VPS. The idea is to make the VPS act as a relay server which routes

packets to the RPi (sort of like “your router in the cloud” if you

will)—while the RPi server only being reachable from within the wireguard

network.

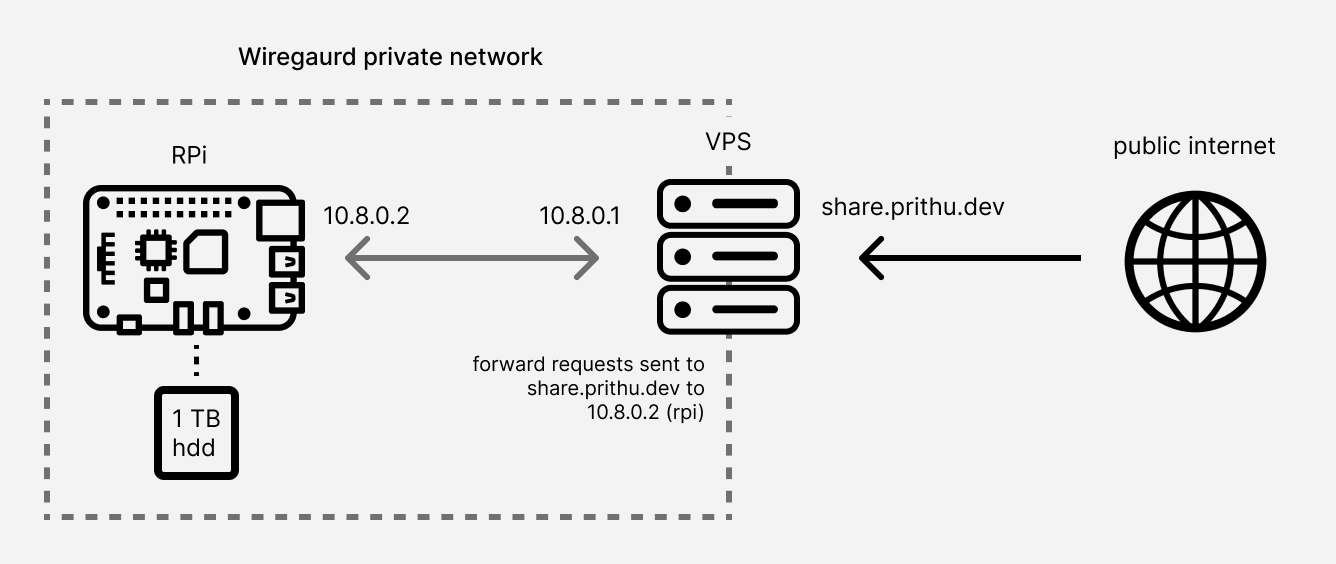

The final setup

This is how the final setup is going to be:

Here’s the wireguard network consisting of the RPi and VPS. The devices are

assigned private IP addresses in the subnet of 10.8.0.0/24.

Setting up the wireguard network

Wireguard makes it super simple to setup a VPN. In fact, it’s one of its aims to be as easy to setup as SSH:

WireGuard aims to be as easy to configure and deploy as SSH. A VPN connection is made simply by exchanging very simple public keys – exactly like exchanging SSH keys …

I’ll try to be brief with this part, at the same time, try explaining most of it (for documentation sake for my future self) but more info can be found in this excellent resource: unoffical wireguard doc.

1. Install wireguard. Wireguard is available pretty much everywhere. You can also compile it from source. The instructions on the website are pretty straight forward and easy to follow. On my ubuntu VPS (and the RPi) it’s just:

$ sudo apt install wireguard

2. Generate the key pair. Wireguard works with simple public-private key

pairs—just like ssh. Each peer in the wireguard network has a public key

associated with it. The wg utility is used to generate these key pairs:

umask 077

wg genkey | tee privatekey | wg pubkey > publickey

3. Configure wireguard. The configuration file for a network is located at

/etc/wireguard/*.conf by default. You can setup and configure multiple

wireguard networks—each having it’s own *.conf file. For example for a

network called wg0, the config file is /etc/wireguard/wg0.conf.

-

On the VPS

[Interface] Address = 10.8.0.1/24 ListenPort = 42069 PrivateKey = <privatekey of VPS> [Peer] PublicKey = <publickey of RPi> AllowedIPs = 10.8.0.2/32 # Peer 2 for example [Peer] PublicKey = <publickey of peer 2> AllowedIPs = 10.8.0.3/32Addressis the IP address associated with the VPS in the network. and the/24suffix means that the VPS can also route traffic not just for itself but also for the whole range of10.8.0.0/24. The VPS is essentially performing the role of a bounce server that routes traffic to/from all the other peers in the network.ListenPortis the port it listens on for connections from peers. This port needs to be publicly reachable, hence punch a hole through the firewall and update the networking security rules of the VPS (something that is easily forgotten).PrivateKeyis the contents of theprivatekeyfile.Each

[Peer]section defines a peer in the network.PublicKeyis the public key of the peer—in this case, the RPi’spublickeyfile.AllowedIPsis simply the IP address range the peer will route traffic for. In this case, it’s a single IP—indicated by the/32suffix—of10.8.0.2. This will be the address of the RPi within the network. More[Peer]sections can be added to add hosts to the network and they’ll all be able to reach each other by routing traffic through the bounce server—forming a virtual mesh network. -

On the RRi

[Interface] Address = 10.8.0.2/32 PrivateKey = <privatekey of RPi> [Peer] PublicKey = <publickey of VPS> AllowedIPs = 10.8.0.1/24 Endpoint = 203.0.113.42:42069 PersistentKeepalive = 25Addressis the IP address that the RPi associates itself within the network. Note the/32suffix means that only a single IP is associated with this host. It tells the network, not a range, but a single IP is reachable by this node.PrivateKeyis the contents of theprivatekeyfile generated on the RPi. The[Peer]section here represents the bounce server (the VPS).PublicKeyis thepublickeyof the VPS.Endpointis the publicly reachable IP and port of the peer—this is the public IP of the VPS and theListenPortfrom the config on the VPS.PersistentKeepaliveis required for peers behind a typical home router performing NAT. It keeps the connection open in order to be able to receive incoming packets even after a long interval of inactivity.2

4. Start wireguard.

sudo wg-quick up wg0

This will bring up the wg0 network interface and setup the link. You can also

use the systemd service file that comes with the package:

sudo systemctl start wg-quick@wg0

Run wg to see if everything is working as expected.

prithu@rpi:~ $ sudo wg

interface: wg0

public key: SomePublickeyForRPi6VzxPWt8sdIj8rkjmzMsxjm8=

private key: (hidden)

listening port: 52912

peer: SomePublicKeyForVPS+px4kBLmGzIrBra2K2Rc3yCw=

endpoint: 203.0.113.42:42069

allowed ips: 10.8.0.0/24

latest handshake: 27 seconds ago

transfer: 265.41 MiB received, 256.75 MiB sent

persistent keepalive: every 25 seconds

The RPi should be reachable at 10.8.0.2 from the VPS and the VPS at

10.8.0.1 from the RPi. You should be able ping the other machine to test

the connection.

Forwarding packets from the VPS

Now that I have the RPi and the VPS in the same wireguard network, I just need

to forward traffic hitting port 80 on the VPS to port 8080 on my RPi, where

the rclone process is listening on. I could simply use a reverse proxy like

nginx or haproxy, but I wanted to make this a learning opportunity and go a

level lower, closer to the networking stack and try using iptables and it’s

NAT capabilities.

A little about iptables

iptables uses netfilter underneath which is a

framework for packet filtering, mangling, rate limiting, logging and lots

more, baked right into the Linux kernel. Netfilter is a kernel-space program

and exposes hooks that let you interact with network packets and perform

actions on them. iptables is an easy to use user-space utility that provides

an interface to netfilter and let’s you create rules and actions that let you

control the fate of each packet that enters or leaves the host. Here’s an

excellent

article

I referred that goes through the architecture of netfilter and iptables. There

are myriad of articles and guides explaining how to use iptables and its syntax

of rule-specifications; so I am not going into detail on that.

NAT’ing the packets

First, lets setup rules in the PREROUTING and POSTROUTING chain in the

nat table. PREROUTING chain in the nat table gives us access to the

DNAT jump target that let’s you change the destination of a packet entering

the host. Similarly, POSTROUTING chain in the nat table gives us access to

the SNAT jump target that lets you change the source of the packet leaving

the host.

sudo iptables -t nat -A PREROUTING -i ens3 -p tcp --dport 80 -j DNAT --to-destination 10.8.0.2:8080

sudo iptables -t nat -A POSTROUTING -o wg0 -p tcp -d 10.8.0.2 --dport 8080 -j SNAT --to-source 10.8.0.1

The first rule changes the destination address of every TCP packet (-p tcp)

hitting port 80 (--dport 80) on the host to 10.8.0.2 and the port to

8080. The -i ens3 specifies the interface for the rule, which is the public

interface of the VPS. Before the packet leaves the VPS destined to the RPi (-d 10.8.0.2 --dport 8080), the second rule changes its source address to the

address of the VPS in the wireguard network (10.8.0.1). This is so that the

RPi replies back to the VPS instead of replying to the original client’s

address. The -o wg0 argument specifies the rule to be applied only for

packets going out through wg0 wireguard interface.

Note on MASQUERADE

MASQUERADE is a special target that is only available in the POSTROUTING

chain of the nat table. It’s a specialized case of SNAT target and

according to the docs it should only be used for dynamically-assigned IP

addresses. i.e if the interface goes down and comes back up with a new IP. In

our case though we have a static IP (10.8.0.1) assigned to the host. I am

sure there are good reasons why not use it if you already have a static ip

assigned and don’t expect it to change; iptables might be performing extra

steps for MASQUERADE targets thus might add some overhead. However, you could

use it with static IP if you are okay with the added overhead. If we were to

use MASQUERADE though, we would not have to mention --to-source argument from

the POSTROUTING rule above.

sudo iptables -t nat -A POSTROUTING -o wg0 -j SNAT MASQURADE

Allowing packets to be forwarded

After being processed by the PREROUTING chain the packet goes through the

FORWARD chain. Here’s what the sequence looks like:

.------------. .---------. .-------------.

ens3--->| PREROUTING +--->| FORWARD +--->| POSTROUTING +---> wg0 (to rpi)

'------------' '---------' '-------------'

Usually the default policy of the FORWARD chain is to DROP the packet. We

need to allow packets to be forwarded. The following two rules allow packets to

be forwarded across the two interfaces:

sudo iptables -A FORWARD -i ens3 -o wg0 -j ACCEPT

sudo iptables -A FORWARD -o wg0 -i ens3 -j ACCEPT

Although the above rules work fine, I could be more specific by including the destination address, port and protocol—making sure we only allow the traffic we want to forward—as a good security measure. But since this is a personal VPS, I don’t mind being a little lax with the rules. Here are more specific rules we can use instead:

sudo iptables -A FORWARD -i ens3 -o wg0 -d 10.8.0.2 -p tcp --dport 8080 -m conntrack --ctstate NEW -j ACCEPT

sudo iptables -A FORWARD -i ens3 -o wg0 -m conntrack --ctstate ESTABLISHED,RELATED -j ACCEPT

sudo iptables -A FORWARD -i wg0 -o ens3 -m conntrack --ctstate ESTABLISHED,RELATED -j ACCEPT

conntrack allows us to use the --ctstate NEW option to allow new

connections through at first. Next we use the ESTABLISHED and RELATED to

allow any packets that are part of an already established or related

connection.

Almost forgot—we need to also enable traffic forwarding at the kernel level by

enabling the net.ipv4.ip_forward kernel parameter, which is disabled by

default.

sysctl -w net.ipv4.ip_forward=1

# to persist across reboot

echo "net.ipv4.ip_forward=1" >> /etc/sysctl.conf

That’s it! Now, all I need to make sure is that port 80 is reachable on the

VPS and point share.prithu.dev to the VPS’s public IP. Visiting

http://share.prithu.dev will render the rclone webdav server’s directory

listing page.

I can use this setup for various other self-hosting projects in the

future—especially when I want to make sure I have the physical access to the

machine providing the service. Forwarding more ports/protocol can be done

simply by copying the same rules (PREROUTING, POSTROUTING) from above and

changing the --dport and -p arguments accordingly and making sure they are

allowed in the FORWARD chain. All in all, this was a good learning

opportunity—especially learning about netfilter and iptables. I thought

iptables was just used as a firewall, while it’s a lot more than just that

and is a pretty versatile tool. While learning about iptables I also came

across nftables which

is a modern successor of iptables which is more flexible and performant.

Uninterupted Power Supply for the RPi

One last thing to add is an UPS. The RPi was powered by an AC adapter, which is not ideal if you are running it as a server since power outages may cause uptime disruptions, even worse, disk corruptions—not something we want while running a server. In order to prevent that, I ordered this micro-UPS to keep my RPi up for enough time until power came back on. This UPS has the correct rating (5V 3A) required for the RPi and has a capacity of 7500 mAh. The UPS seamlessly switches over to battery power without disrupting the Pi. It’s a life saver and keeps the RPi up reliably during outages.

-

something like this script ↩︎